This essay explores themes in Philosophy. For essays on other topics such as Politics, Art & Culture, Theology, or Plato, please see the topical archive at Plato For The Masses.

Apologies for the dearth of essays in June; I’ve been buried in grading and teaching work as my academic year prepares to wrap on July 2. Yes, July 2 – some quirk with the calendar in 2025 pushed everything late this year. Easter came at the latest possible date and my Spring quarter, which included two preps, doesn’t wrap until July 2. Nonetheless, I have a number of partially written Substack essays in the queue, and they’ll be releasing in the coming weeks, so lots to look forward to this summer, including (finally!) my official ‘inaugural’ essay describing the purpose of Plato For The Masses and where my writing will take us in the near future. Thank you for your patience and participation as I work to grow our community!

This is an essay on knowledge and trust. Life today is lived in the wake of the printing press, the telephone, television, the internet, and now social media. Together, these technological innovations have produced a social environment that operates at a scale, speed, and density orders of magnitude beyond the functional capacity of our human sensory and nervous systems. While our brains continue to rewire themselves to navigate our rapidly evolving information landscape, it is only with great effort and care that we have any success knowing what to believe in this brave new world we’ve made for ourselves. We are not born capable of thinking well and believing truth. Only if we train in virtue and exercise the intellectual virtues responsibly will we reliably attain knowledge.

We gather information to know what to believe. Our beliefs constitute our picture of our world: what there is and what is important. Most information is merely noise, and much is even false. Information is anything that communicates, but not every communication is true. Truth is the goal of our beliefs. We want to develop a true picture of our world. If we don’t, then we might step out into oncoming traffic because we believe the street is safe to cross.

Unfortunately, our beliefs don’t always aim at truth. We often adopt beliefs because of how our parents raised us, or because of our wider community’s perspective, or because of our prejudice for or against certain descriptions of the world. Beliefs can signal membership in a group, a certain social status, and they can even be tools of revenge or shame. If our goal is to only adopt beliefs that are true, our believing practices need some help.

When our beliefs don’t have help, we call them opinions. When we form beliefs while indifferent or uncertain as to their truth, then we have opinions. Our opinions might accidentally be true, but whether or not they are true has no bearing on our having them. We want to win the argument, or show that we’re smarter than our friends, or maybe we just don’t like the political party of the other side and don’t want to credit them with having done something right. So we insist that we have a right to our opinion and can believe whatever we want.

Opinions never amount to knowledge. We never know whether our opinions are true, even when we get lucky and they are true. If we want to know that our beliefs are true, then it’s not enough to have beliefs, and it’s not enough for them to be true. What we need is to only have beliefs because we have good reasons for thinking they are true. Only when we have true beliefs with an account, with some responsible reasons for thinking they are true, do those particular beliefs constitute knowledge. Since we believe in order to form an accurate picture of our world, we want to pursue knowledge and avoid opinions.

An accurate picture of our world is something we share, unlike our private tastes and preferences. Preferences are our personal likes and dislikes. We might prefer mint chip to chocolate ice cream; we might prefer living in the city to the countryside; we might prefer not associating with people who do or don’t have college degrees. Our preferences describe ourselves, not our world, so our preferences can never become universal beliefs. Just because I prefer mint chip ice cream does not mean you should prefer mint chip ice cream. You are not me. Groups can also have preferences. People who are financially poor tend to favor heavily taxing the rich, while the rich tend to not share that preference.

The situation is quite different with facts. There can be no ‘alternative facts’ because a fact is a true description of the world. Striving to ascertain the facts is just another way of saying we’re pursuing shared knowledge; that is, universal beliefs that all of us should believe whenever we’re seeking to understand that particular bit of the world. It is a fact that there was no rock ‘n roll music before 1900 A.D.; it is a fact that the United States is in North America; it is a fact that the human population explosion over the last hundred years is due in part to the development of vaccines. We call things facts as a way to signal to each other that these are descriptions of the world we should all adopt, that they do not reflect just any one person or group’s private preferences.

Let’s call someone who is forming and letting go of beliefs a believer. A conscientious believer will be someone who carefully distinguishes between their preferences and the facts. They will eschew opinions and try to develop reasons for their beliefs so that their beliefs amount to knowledge.

However, no one person has the time or the energy to develop reasons for everything they believe. We either have to get on without knowing very much, or we have to pool our resources and try to share our knowledge. This allows all of us to develop a rich collection of beliefs without having to personally justify all of them. We can have a division of labor in developing reasons for each belief.

Sometimes though, we cannot even share our reasons for belief. In those cases, we communicate the facts to each other through our epistemic authority. A person with genuine epistemic authority is someone we trust to provide us with knowledge. Parents, teachers, reporters, experts, and public officials all carry the responsibility of upholding the bonds of epistemic trust in a community. These are people that we are trusting to only share with us what they know, and that if pressed, could give us a good account of how they know what they know.

We have identified three major areas of concern to each of us as believers. As believers we have to (1) develop an account supporting beliefs we adopt under our own authority, (2) discern whether the reasons others give for their beliefs are good reasons, and (3) discern who are the trustworthy authorities we can rely on to share with us what they know when their reasons exceed our learning or we lack the time to examine their reasons for ourselves.

Thankfully, beliefs in all three areas of concern can be readily supported through the regular practice of the intellectual virtues. An intellectual virtue is a characteristic of our thinking and believing practices that empowers us towards what is true and away from what is false. The more we practice intellectual virtues, the more we become people who believe only what is true. Practicing the intellectual virtues ourselves helps us to carefully construct our own reasons for belief and to critically evaluate reasons offered by others. Whenever we are faced with arguments we cannot understand or we lack the time to engage with arguments, we should only trust knowledge from authorities who evidently practice the intellectual virtues themselves. In other words, a trusted authority is someone who is visibly and regularly intellectually virtuous.

I.

Across all the intellectual virtues, a love of truth is a defining ingredient. A virtuous believer loves the truth more than being seen as wise, or being right, or winning an argument. There are many, many intellectual virtues, but we will focus on three central virtues exemplified by anyone who loves the truth: curiosity, honesty, and carefulness.

Curiosity is a desire to acquire knowledge for its own sake. When we are curious, we have no further goal or motivation beyond our desire to unravel some puzzle, explore some new phenomenon, or answer a difficult question. French philosopher René Descartes describes curiosity as the experience of wonder, writing,

When our first encounter with some object surprises us and we find it novel, or very different from what we formerly knew or from what we supposed it ought to be, this causes us to wonder and to be astonished at it. Since all this may happen before we know whether or not the object is beneficial to us, I regard wonder as the first of all the passions. (The Passions of the Soul, II.53)

When practicing curiosity, we are not looking for applications that will secure a second round of funding for a tech startup, or juicy gossip we can use to blackmail someone we don’t like, or even merely where to find the nearest sandwich shop. While the discoveries of our curiosity may lead to such useful applications, they also may not, and they need not, because the satisfaction of discovery is the primary incentive for our inquisitiveness.

A curious person is open-minded about what they might discover. They do not determine in advance of their investigation how the world must be or what is important. The truly curious are willing to ‘let the chips fall where they may,’ to ‘follow the evidence wherever it leads.’ Curious people do not try to make the world fit with their preconceived notions of it; rather, they allow the world to surprise them and change their minds. They fit their minds to the facts rather than rewriting the facts to fit what they already think or what they want to be true.

The practice of curiosity is complemented by a resolute honesty. Honesty is one of the most misunderstood of the intellectual virtues. The decadence of our modernity has watered-down our concept of honesty, so that for most of us an honest person is simply someone who always tells the truth when asked. Conceiving honesty this way leads predictably to angst-filled conundrums like whether an honest person should tell the truth when the slaveowner knocks at their door and they are indeed harboring fugitive slaves. A honest person is not someone who always tells the truth, because sometimes being honest means not telling the truth.

Rather, in the virtue tradition, honesty is a reverence for the truth such that the honest person will not distort the truth for any reason apart from upholding that reverence. Reverence is something like awe; to treat something with reverence is to acknowledge it as sacred, holy, precious. Just as a faithful Muslim will not soil the Qu’ran, and a doting parent will not harm their newborn, so the honest person cherishes the truth and keeps it from distortion and misuse. We are often tempted to lie or mislead or omit or obscure the truth when it is embarrassing or reveals that we made a mistake or it will disadvantage our political party or social group. Yet in the face of such temptations, the honest person will tell the truth because the truth matters to them more than manipulating the information landscape to their personal advantage.

In the example of the fugitive slaves, the honest person lies to the slaveowner (and thus obscures the truth for them) because their reverence for the truth means they are willing to guard it from those who would misuse the truth, who do not value the truth for its own sake. The honest person protecting slaves refugees is not lying for their own advantage, but to safeguard the people they are protecting. People who love the truth also love what is good and just.

An honest person will not deliberately ignore or suppress evidence against their views. They will never intentionally set a higher evidential standard for contrary views than for their own, so as to make it harder to accept those contrary views than it should be. They will never accept rationalizations for their own views that they would reject if offered by an opponent. Honesty means we do not try to make it more likely that our beliefs appear true and the beliefs of those we disagree with appear false. To be honest means revering the truth whether it aligns with what we want to be true or not.

II.

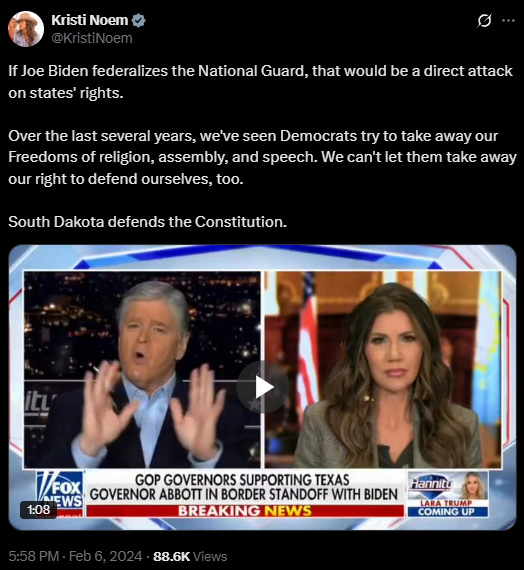

When Kristi Noem was Governor of South Dakota, she opposed the federalization of a state’s National Guard over the objections of a state Governor (although President Biden had no plans to do any such thing). She wrote in a Twitter post on 06 February 2024, “If Joe Biden federalizes the National Guard, that would be a direct attack on states’ rights.”

She later said at the CPAC conference on 23 February 2024,

I was alarmed recently to hear Democrats encouraging Biden to federalize the National Guard under Title 10 in order to take them away from the control of governors and take away my ability to be their commander-in-chief of the National Guard.

This was in response to suggestions that Biden should federalize the Texas and South Dakota National Guard soldiers then serving on the Texas border. The National Guard were preventing federal U.S. Border Patrol agents from patrolling a key stretch of the border along the Rio Grande. In response to an emergency petition by the Biden administration, the U.S. Supreme Court permitted federal agents to cut concertina fencing that the National Guard had erected for the purpose of preventing Border Patrol entering the area. Yet Gov. Abbott refused to yield the territory to federal Border authorities, resulting in the sitting President being unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States (nonetheless, Biden never federalized any National Guard units).

According to Gov. Noem, National Guard soldiers should not be federalized by the President contrary to the wishes of a state Governor if those Guard soldiers are already engaged in a mission under the command of the Governor.

In 07 June 2025, Donald Trump federalized the California National Guard over the objections of that state’s Governor, despite the National Guard already being engaged on a mission under the command of the Governor to support border control. Trump’s justification for federalizing the Guard was that rioters in Los Angeles were interfering with federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents to a degree that Trump was unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States within the city. The National Guard was activated to provide additional security for ICE operations in Los Angeles.

If Kristi Noem, now Secretary of Homeland Security, were honest she would object to Trump’s mobilization of the National Guard over the protestations of the state Governor. She would continue to stand up for state’s rights and every Governor’s authority as commander-in-chief of the National Guard. Trump’s actions should not be held to a different standard than President Biden’s actions. If practicing honesty, Noem would not distort the truth of either the situation in Los Angeles or the previous situation in Texas to disfavor President Biden or advantage Trump.

Instead of standing up for California’s state rights or Gavin Newsom’s authority as commander-in-chief of the National Guard, Kristi Noem said on 08 June 2025 in an interview with CBS’s Face the Nation,

Governor Newsom has proven that he makes bad decisions. The President knows that he makes bad decisions, and that's why the President chose the safety of this community over waiting for Governor Newsom to get some sanity. And that's one of the reasons why these National Guard soldiers are being federalized so they can use their special skill set to keep peace.

If President Biden had offered the same rationalization for relieving Texas Gov. Abbott of his authority over the state National Guard, Kristi Noem would not have accepted it. This anecdote illustrates Noem’s dishonesty in representing the relationship between the law and an immigration situation in Texas favorably to a Republican Governor and disfavorably to a Democrat President, and then representing a similar relationship in California disfavorably to a Democrat Governor and favorably to a Republican President.

So one way to test whether someone is a trustworthy authority for knowledge is whether they are willing to tell the truth about their own side even when it’s disadvantageous, and tell the truth about an opposing side even when it might benefit their opponent. We should trust people who demonstrate that they revere the truth more than winning the public debate or pleasing the head of their political party.

An honest person cannot adequately revere the truth without practicing accuracy in their judgments. Accuracy is the practice of describing the world and its importance close enough to the truth. An accurate description does not selectively highlight some aspects of a situation while obscuring other aspects in ways that are favorable to what we want people to believe.

For example, when Kristi Noem held a press conference in Los Angeles following the federalization of the National Guard in June 2025, the headlines for the event placed different emphases on what transpired at the press conference. The Fox News headline read, “Democrat senator forcibly removed after crashing DHS Secretary Noem's press conference.” In contrast, the local Los Angeles station KTLA posted this headline: “Sen. Alex Padilla forcibly removed, handcuffed after confronting DHS Secretary Noem during press conference.” Regardless of which headline we think is the more accurate, they each frame the press conference in a manner that implies certain value judgments. For the Fox News report, Sen. Padilla “crashed” the press conference, implying that he was a disrupter or an agitator and authorities were justified in having him removed. The local CW affiliate described Sen. Padilla as confronting Noem, suggesting that she was doing something questionable and he was merely standing up to her. In one report, Padilla is less sympathetic while Noem is more sympathetic; in the other report, the opposite.

Accurate judgments require being willing to describe facts as they would be seen by someone with no personal stake in what everyone believes the facts to be, even if that means describing the facts in a manner disadvantageous to our own side. When President Biden said in his 2024 Presidential debate that “the Border Patrol endorsed me, endorsed my position” on immigration enforcement, a more accurate description would have been that the Border Patrol’s union had endorsed the bipartisan security bill Biden favored. Endorsing a bill is not the same as endorsing a candidate or their position.

When Trump said via Truth Social on 09 June 2025 that “if we had not [sent in the National Guard], Los Angeles would have been completely obliterated,” this is a wildly inaccurate description of the situation in Los Angeles. As Trump’s own legal team has testified in Newsom v. Trump, the National Guard has played no law enforcement role at all in addressing rioters or vandalism in Los Angeles. Their sole function is to add security to federal buildings and to accompany ICE agents during raids. All instances of rioting and vandalism have been sufficiently addressed by LAPD officers and SWAT. There was never any threat that local and state law enforcement was unable to maintain civic order in the city.

Politicians and media pundits have throughout human history been inaccurate reporters of fact, relying on dishonest descriptions to either hold onto their own power/audience or to dislodge the power/audience of a rival. It is an unfortunate characteristic of democracy in an age of mass media that honesty in leaders or commentators is rarely required.

Witness their penchant for hyperbole. Cable programs like CNN and MSNBC regularly provide headlines like “Trump slams Powell over interest rates” and “Biden slams Trump administration’s cuts to Social Security.” Elected and appointed leaders flippantly invoke words like ‘fascism,’ ‘insurrection,’ ‘outrageous,’ ‘deplorable,’ ‘unconstitutional,’ ‘invasion,’ and ‘coup’ for purposes that are profoundly dishonest.

They have a similar habit of employing euphemism. If Democrats call the Jan. 6th riot “an insurrection,” Republicans might call it a “energetic protest.” Republicans regularly like to cut “waste, fraud, and abuse” at the IRS, when I would say a more accurate description is they are defunding the tax police. Abortion rights advocates speak of “fetal remains” rather than call an aborted baby the corpse of a child. President Johnson famously sent American troops to Vietnam on an “assistance and advisory mission” and continued using mild descriptions for military operations even as he escalated U.S. involvement into a full-scale war. When I was a soldier in Iraq, our enemies were called “insurgents” but local nationals allied with us were called “freedom fighters.” I learned when speaking with an ‘insurgent’ prisoner that on their side the terms were exactly the opposite. We can use hyperbole to significantly overstate the facts, and we can use euphemism to significantly downplay the facts. Neither communicates accurate judgments, so neither are characteristic of honest people.

III.

We distinguished knowledge from opinions earlier by saying that we achieve knowledge when our beliefs are true and we have good reasons for holding those beliefs. In order to be confident that we have good reasons for our beliefs, virtuous believers are careful when thinking through whether something is true or not. Carefulness is the practice of giving the time and scrutiny to all the relevant arguments and evidence for and against a claim proportionate to the importance of the claim, and taking into account our biases and limitations. We don’t need to be super careful about speculation of life on other planets if we’re ordinary folks going about our lives; but if we’re a professional astrobiologist preparing to publish a scientific article claiming there is life in another solar system within our galaxy, then we should be very careful!

Carefulness is not only about investing the requisite time and conscientious scrutiny to the arguments and evidence; it’s also about reflecting on our own biases and limitations. Whenever we investigate a question, we should interrogate our own investigative process by asking: Is my judgment based on an incomplete picture? Have I read arguments from different perspectives? Am I ignoring inconvenient evidence? What alternative conclusions are consistent with my evidence? Does my evidence really provide strong support for believing the claim? Or does it support suspending judgment or even disbelief? Am I inclined to always believe voices aligned with ‘my side’ and disbelieve voices aligned with ‘their side’? What experiences might I be lacking that would be necessary to appreciate the importance of the relevant factors?

Being careful means ensuring that if we are mistaken about our arguments or our evaluation of the evidence, we’ll find out. During the 2024 border crisis, I continually worried that, whatever President Biden’s failure to establish adequate border policies, there was nothing he could do that would receive favorable appreciation by his Republican critics. When they accused Biden of failing to enforce the border, it was never clear what would change their minds. In epistemology, we call this falsification. Part of practicing carefulness is ensuring that when we make a claim, we establish in advance what practically achievable conditions would have to be met in order for us to change our minds about that claim. When Biden was criticized for not securing the border, what actions could he take that would constitute securing the border to the satisfaction of his critics?

After reaching peak illegal immigrant encounters of more than 250,000 in December 2023, the Biden administration responded to criticism by taking action. By August 2024, border contacts had dropped to 58,000, an astonishing reduction of 77% in nine months. While this accomplishment does not excuse Biden’s lack of urgency in previous years, it seemed like Biden had made a good faith, reasonable attempt to undertake the very actions of securing the border the Republicans had asked for. Yet I have been unable to find a single Republican leader who had criticized Biden on the border later acknowledging that he had taken constructive actions to stem the waves of immigrants.

We would have a much more accountable political culture if leaders and media commentators were required to present falsifiable evidence for their claims and to set falsifiable conditions for their criticisms of rivals. When that evidence is falsified, they need to retract their claims and admit their errors. When those conditions are met, they need to withdraw their criticism and commend their rival for a job well done. By making vague and unfalsifiable accusations or ignoring evidence to the contrary, people demonstrate that they are not open to correction, to admitting when they are wrong, or to giving credit where credit is due.

A willingness to falsify one’s own beliefs reflects caring more about the truth than being right. One of Plato’s great adages was that it is better to be refuted than to be affirmed. That is so counterintuitive in our contemporary culture! We obsess about appearances, concerned that we always appear to be in the right. We strive to always have the upper hand, never admit defeat, never admit that we’re wrong.

But a trustworthy and virtuous believer is someone who values being refuted, corrected, shown the error of their ways. A careful thinker committed to falsifying their beliefs is someone who will go out of their way to find out if they are wrong. They will put themselves into positions where they are likely to be proven wrong. They want to test whether they’ve made a mistake. Being virtuous means we place far less value on the praise of others affirming what we believe. We’re not looking to be agreed with, but to be disagreed with. People who agree with us will probably make the same mistakes and oversights and suffer the same biases as ourselves. It is only through vigorous disagreement and being open-minded to the ideas and perspectives of those we disagree with that we are best positioned to discover our mistakes and change our minds.

Taking these virtues together, we should only trust people as epistemic authorities when they visibly and consistently demonstrate that they are virtuous believers; that is, that they are curious, honest, and careful with the beliefs they form and share with others. We discern who to trust by looking for indicators of curiosity, honesty, and carefulness. We look for a commitment to the truth for its own sake, not for some ulterior benefit. We only rely on authorities who permit the world and its importance to overturn their own preconceived expectations. We watch for a willingness to admit the truth even when it’s disadvantageous to do so. We demand accuracy in judgment, not exaggeration or distortion. We only listen to authorities who have a track record of making evidence-based decisions and providing accessible arguments for their beliefs, and who are willing to have those decisions corrected by new evidence or who are willing to change their minds when conditions are met that they themselves put forward.

We should only trust as authorities for knowledge those sources who are more loyal to the truth than to a political party, an ideology, a team, a tribe, and most of all private preferences. If someone aims to get rich by pushing a belief, or to avoid prison by pushing a belief, or to gain political power or social prestige by pushing a belief, then they are not trustworthy. If a media commentator has an incentive to make outlandish or watered-down claims in order to get clicks or views, they are not trustworthy. If any person seems like they are trying to win a debate or get the best of another person, rather than curiously understand the world better, they are not trustworthy.

The people worth trusting are those who run towards accountability to the truth, not away from it. Trustworthy people never try to spin things in their favor, they never eschew oversight and transparency, and they demonstrate a willingness to set aside their own advantage out of love for the truth. That’s why as a rule of thumb, I don’t pay much attention to a source who criticizes the other side. I know that Democrats have a black belt in criticizing Republicans, and that Republicans have attained grandmaster status in criticizing Democrats. Such criticisms carry little credibility. I only trust Democrats who are more interested in and willing to criticize other Democrats, to put their own house in order. I only trust Republicans who are more loyal to the Constitution than they are to their party or Donald Trump. Those are the visible signs of a love of the truth. The truth is too important to sacrifice for partisan loyalty. Because the truth is nothing less than our one chance to live in a common world – and through our shared commitment to the truth, make it a better world.